Historical

Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Exposure to smallpox during early Spanish attempts to convert the Native populations to plantation slavery exterminated all 3.5 million Native inhabitants of the region.

Africa

African epidemics

Variola lesions on chest and arms

One of the oldest records of what may have been an encounter with smallpox in Africa is associated with the elephant war circa AD 568 CE, when after fighting a siege in Mecca, Ethiopian troops contracted the disease which they carried with them back to Africa.[citation needed]

Arab ports in Coastal towns in Africa likely contributed to the importation of smallpox into Africa, as early as the 13th century, though no records exist until the 16th century. Upon invasion of these towns by tribes in the interior of Africa, a severe epidemic affected all African inhabitants while sparing the Portuguese. Densely populated areas of Africa connected to the Mediterranean, Nubia and Ethiopia by caravan route likely were affected by smallpox since the 11th century, though written records do not appear until the introduction of the slave trade in the 16th century.[3]

The enslavement of Africans continued to spread smallpox to the entire continent, with raiders pushing farther inland along caravan routes in search of people to enslave. The effects of smallpox could be seen along caravan routes, and those who were not affected along the routes were still likely to become infected either waiting to be put onboard or on board ships.[3]

Smallpox in Angola was likely introduced shortly after Portuguese settlement of the area in 1484. The 1864 epidemic killed 25,000 inhabitants, one third of the total population in that same area. In 1713, an outbreak occurred in South Africa after a ship from India docked at Cape Town, bringing infected laundry ashore. Many of the settler European population suffered, and whole clans of the Khoisan people were wiped out. A second outbreak occurred in 1755, again affecting both the white population and the Khoisan. The disease spread further, completely eradicating several Khosian clans, all the way to the Kalahari desert. A third outbreak in 1767 similarly affected the Khoisan and Bantu peoples. But the European colonial settlers were not affected nearly to the extent that they were in the first two outbreaks, it has been speculated this is because of variolation. Continued enslavement operations brought smallpox to Cape Town again in 1840, taking the lives of 2500 people, and then to Uganda in the 1840s. It is estimated that up to eighty percent of the Griqua tribe was exterminated by smallpox in 1831, and whole tribes were being wiped out in Kenya up until 1899. Along the Zaire river basin were areas where no one survived the epidemics, leaving the land devoid of human life. In Ethiopia and the Sudan, six epidemics are recorded for the 19th century: 1811–1813, 1838–1839, 1865–1866, 1878–1879, 1885–1887, and 1889–1890.[31]

Epidemics in the Americas

| Year | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1520–1527 | Mexico, Central America, South America | Smallpox kills 5-8 millions of native inhabitants of Mexico. Unintentionally introduced at Veracruz with the arrival of Panfilo de Narvaez on April 23, 1520, and was credited with the victory of Cortes over the Aztec empire at Tenochtitlan (present-day Mexico City) in 1521. Kills the Inca ruler, Huayna Capac, and 200,000 others and weakens the Incan Empire. |

| 1561–1562 | Chile | No precise numbers on deaths exist in contemporary records but it is estimated that natives lost 20 to 25 percent of their population. According to Alonso de Góngora Marmolejo, so many Indian laborers died that the Spanish gold mines had to shut down.[33] |

| 1588–1591 | Central Chile | A combined smallpox, measles and typhus plague strikes Central Chile contributing to a decline of indigenous populations.[34] |

| 1617–1619 | North America northern east coast | Killed 90% of the Massachusetts Bay Indians |

| 1655 | Chillán, Central Chile | An outbreak of smallpox occurred among refugees from Chillán as the city was evacuated amidst the Mapuche uprising of 1655. Spanish authorities put this group in effective quarantine decreeing death sentences for anyone crossing Maule River north.[35] |

| 1674 | Cherokee Tribe | Death count unknown. Population in 1674 about 50,000. After 1729, 1738, and 1753 smallpox epidemics their population was only 25,000 when they were forced to Oklahoma on the Trail Of Tears. |

| 1692 | Boston, MA | |

| 1702–1703 | St. Lawrence Valley, NY | |

| 1721 | Boston, MA | A British sailor disembarking the HMS Seahorse brought smallpox to Boston. 5759 people were infected and 844 died. |

| 1736 | Pennsylvania | |

| 1738 | South Carolina | |

| 1770s | West Coast of North America | At least 30% (tens of thousands) of the Northwestern Native Americans die from smallpox[36][37] |

| 1781–1783 | Great Lakes | |

| 1830s | Alaska | Reduced Dena’ina Athabaskan population in Cook Inlet region of southcentral Alaska by half.[38] Smallpox also devastated Yup’ik Eskimo populations in western Alaska. |

| 1836–1840 | Great Plains | 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic |

| 1860–1861 | Pennsylvania | |

| 1862 | British Columbia, Washington state & Russian America | Known as the Great Smallpox of 1862, an outbreak of smallpox in a large encampment of all indigenous peoples from around the colony on June 10, 1862, dispersed by order of the government to return to their homes, resulted in the deaths of 50-90% of the indigenous peoples in the region[39][40][41][42][43] |

| 1865–1873 | Philadelphia, PA, New York, Boston, MA and New Orleans, LA | Same period of time, in Washington D.C., Baltimore, MD, Memphis, TN, Cholera and a series of recurring epidemics of Typhus, Scarlet Fever and Yellow Fever |

| 1869 | Araucanía, southern Chile | A smallpox epidemic breaks out among native Mapuches, just some months after a destructive Chilean military campaign in Araucanía.[44] |

| 1877 | Los Angeles, CA | |

| 1880 | Tacna, Peru | Tacna hosted the combined armies of Peru and Bolivia before being defeated by Chile in the Battle of Tacna. Before it fell to Chileans in late May 1880 infectious diseases were widespread in the city with 461 deaths of smallpox in the 1879-1880 period, making up 11.3% of all registered deaths for the city in the same period.[45] |

| 1902 | Boston, Massachusetts | Of the 1,596 cases reported in this epidemic, 270 died. |

| 1905 | Southern Patagonia, Chile | A smallpox epidemic hits Tehuelche communities in Magallanes Territory, Chile.[46][47] Cacique José Mulato died in the epidemic.[47] |

After first contacts with Europeans and Africans, some believe that the death of 90–95% of the native population of the New World was caused by Old World diseases.[48] It is suspected that smallpox was the chief culprit and responsible for killing nearly all of the native inhabitants of the Americas. For more than 200 years, this disease affected all new world populations, mostly without intentional European transmission, from contact in the early 16th century until possibly as late as the French and Indian Wars (1754–1767).[49]

In 1519 Hernán Cortés landed on the shores of what is now Mexico and what was then the Aztec Empire. In 1520 another group of Spanish arrived in Mexico from Hispaniola, bringing with them the smallpox which had already been ravaging that island for two years. When Cortés heard about the other group, he went and defeated them. In this contact, one of Cortés’s men contracted the disease. When Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan, he brought the disease with him.[citation needed]

Soon, the Aztecs rose up in rebellion against Cortés and his men. Outnumbered, the Spanish were forced to flee. In the fighting, the Spanish soldier carrying smallpox died. Cortés would not return to the capital until August 1521. In the meantime smallpox devastated the Aztec population. It killed most of the Aztec army and 25% of the overall population.[50] The Spanish Franciscan Motolinia left this description: “As the Indians did not know the remedy of the disease…they died in heaps, like bedbugs. In many places it happened that everyone in a house died and, as it was impossible to bury the great number of dead, they pulled down the houses over them so that their homes become their tombs.”[51] On Cortés’s return, he found the Aztec army’s chain of command in ruins. The soldiers who still lived were weak from the disease. Cortés then easily defeated the Aztecs and entered Tenochtitlán.[52] The Spaniards said that they could not walk through the streets without stepping on the bodies of smallpox victims.[53]

The effects of smallpox on Tahuantinsuyu (or the Inca empire) were even more devastating. Beginning in Colombia, smallpox spread rapidly before the Spanish invaders first arrived in the empire. The spread was probably aided by the efficient Inca road system. Within months, the disease had killed the Incan Emperor Huayna Capac, his successor, and most of the other leaders. Two of his surviving sons warred for power and, after a bloody and costly war, Atahualpa become the new emperor. As Atahualpa was returning to the capital Cuzco, Francisco Pizarro arrived and through a series of deceits captured the young leader and his best general. Within a few years smallpox claimed between 60% and 90% of the Inca population,[54] with other waves of European disease weakening them further. A handful of historians argue that a disease called Bartonellosis might have been responsible for some outbreaks of illness, but this opinion is in the scholarly minority.[55] The effects of Bartonellosis were depicted in the ceramics of the Moche people of ancient Peru.[56]

Even after the two largest empires of the Americas were defeated by the virus and disease, smallpox continued its march of death. In 1561, smallpox reached Chile by sea, when a ship carrying the new governor Francisco de Villagra landed at La Serena. Chile had previously been isolated by the Atacama Desert and Andes Mountains from Peru, but at the end of 1561 and in early 1562, it ravaged the Chilean native population. Chronicles and records of the time left no accurate data on mortality but more recent estimates are that the natives lost 20 to 25 percent of their population. The Spanish historian Marmolejo said that gold mines had to shut down when all their Indian labor died.[57] Mapuche fighting Spain in Araucanía regarded the epidemic as a magical attempt by Francisco de Villagra to exterminate them because he could not defeat them in the Arauco War.[33]

In 1633 in Plymouth, Massachusetts, the Native Americans were struck by the virus. As it had done elsewhere, the virus wiped out entire population groups of Native Americans. It reached Mohawks in 1634,[58] the Lake Ontario area in 1636, and the lands of the Iroquois by 1679.[59]

AIDS in Haiti

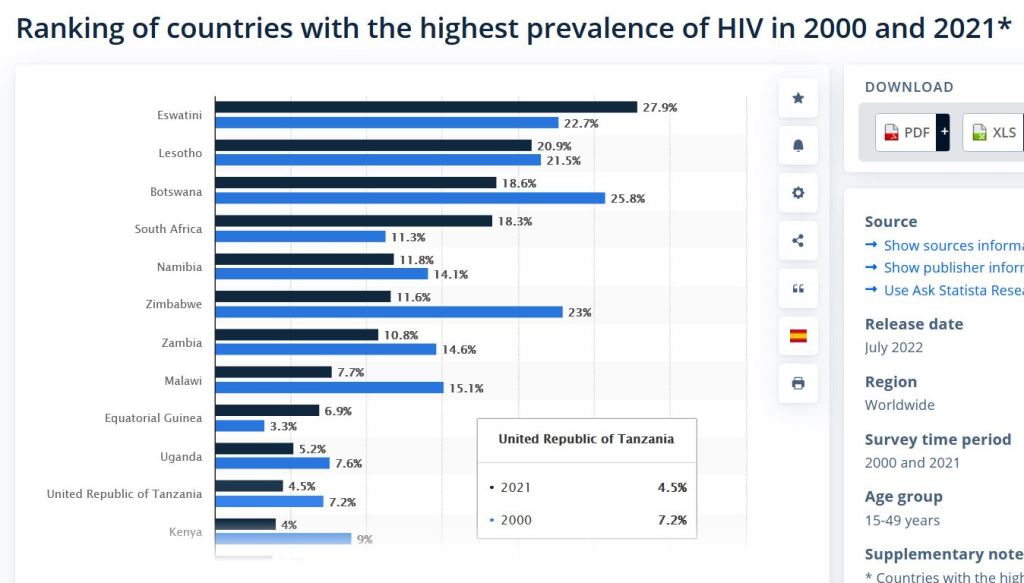

With an estimated 150,000 people living with HIV/AIDS in 2016 (or an approximately 2.1 percent prevalence rate among adults aged 15–49), Haiti has the most overall cases of HIV/AIDS in the Caribbean and its HIV prevalence rates among the highest percentage-wise in the region.[3] There are many risk-factor groups for HIV infection in Haiti, with the most common ones including lower socioeconomic status, lower educational levels, risky behavior, and lower levels of awareness regarding HIV and its transmission.[4][5]

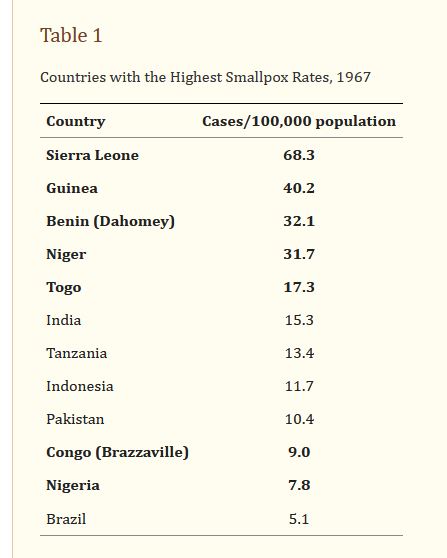

AIDS in Sierra Leon

Sierra Leone is a low-income West African country that has dealt with waves of economic, political, and public health challenges in its recent past, including a decade-long brutal civil war and the Ebola epidemic of 2014-2016. The HIV/AIDS epidemic, which has raged on in the country since 1987, has long been characterized as stable.

AIDS in Benin

he number of adults and children living with HIV/AIDS in Benin in 2003 was estimated by the Joint United Nations Programme for HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) to range between 38,000 and 120,000, with nearly equal numbers of males and females. A recent study conducted by the National AIDS Control Program estimated the number of people living with HIV/AIDS to be 71,950. In 2003, an estimated 6,140 adults and children died of AIDS. Benin has a well-functioning system of antenatal HIV surveillance; in 2002, the median HIV prevalence at 36 antenatal clinics was 1.9%. Another study in 2002 showed an overall prevalence of 2.3% among adults in Cotonou, Benin’s largest city.[1]

AIDS in Niger

Prevalence

2007 estimates put the number of HIV positive Nigeriens at 60,000 or 0.8% of total population, with 4,000 deaths in that year.[1] United Nations estimates in 2008 gave similar figures, giving Niger one of the lowest infection rates on the continent.[2]

2008 estimates ranged from 44,000 to 85,000 people living with HIV in a nation of around 14 million, with an adult (aged 15 to 49) prevalence rate of between 0.6% and 1.1%. Adults aged 15 and up living with HIV were estimated to range from 42,000 to 81,000, with women of this age range making up about a third (12,000 to 26,000). Estimates of children (under 14) living with HIV were between 2,500 and 4,200. Total deaths were estimated to be between 3,000 and 5,600 per year. Aids orphans (under 17) were estimated at between 18,000 and 39,000.[2]

AIDS in Tanzania

Tanzania faces generalized HIV epidemic which means it affects all sections of the society but also concentrated epidemic among certain population groups. The prevalence of HIV/AIDS in Tanzania is characterised by substantial across age, gender, geographical location and socioeconomic status implying difference in the risk of transmission of infection.[1] In 2019, among 1.7 million people living with HIV/AIDS, the prevalence was 4.6% and 58,000 new HIV infection among 15–49 years old, and 6,500 new infections among children below 15 years old,[1] 50% of all new infections are between 15 – 29 years of age group.[2] Report from Tanzania PHIA of 2016/17 shows that HIV prevalence among women is higher (6.2%) than men (3.1%).[3] The prevalence of HIV is less than 2% among 15-19 years for both males and females and then increases with age for both sexes.[1]

AIDS in Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is facing a large-scale growing HIV/AIDS epidemic, with an estimated national average adult prevalence of 4% and 1.19 million people living with HIV/AIDS at the end of 2005. The principal mode of transmission is heterosexual.

AIDS in Nigeria

HIV/AIDS originated in Africa during early 20th century and is a major public health concern and cause of death in many African countries. AIDS rates varies significantly between countries, though the majority of cases are concentrated in Southern Africa. Although the continent is home to about 15.2 percent of the world’s population,[1] more than two-thirds of the total infected worldwide – some 35 million people – were Africans, of whom 15 million have already died.[2]Eastern and Southern Africa alone accounted for an estimate of 60 percent of all people living with HIV[3] and 70 percent of all AIDS deaths in 2011.[4] The countries of Eastern and Southern Africa are most affected, AIDS has raised death rates and lowered life expectancy among adults between the ages of 20 and 49 by about twenty years.[2] Furthermore, the life expectancy in many parts of Africa is declining, largely as a result of the HIV/AIDS epidemic with life-expectancy in some countries reaching as low as thirty-nine years.

Conclusion

While there is some correlation in is not sufficient to prove causation even though it is suspicious,