Bivalent Vaccine

As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health. Learn more about our disclaimer.

Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023 Jun; 10(6): ofad209.

Published online 2023 Apr 19. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofad209

PMCID: PMC10234376

PMID: 37274183

Effectiveness of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Bivalent Vaccine

Nabin K Shrestha,Patrick C Burke, Amy S Nowacki, James F Simon, Amanda Hagen, and Steven M Gordon

Author informationArticle notesCopyright and License informationDisclaimer

Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether a bivalent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine protects against COVID-19.

Methods

The study included employees of Cleveland Clinic in employment when the bivalent COVID-19 vaccine first became available. Cumulative incidence of COVID-19 over the following 26 weeks was examined. Protection provided by vaccination (analyzed as a time-dependent covariate) was evaluated using Cox proportional hazards regression, with change in dominant circulating lineages over time accounted for by time-dependent coefficients. The analysis was adjusted for the pandemic phase when the last prior COVID-19 episode occurred and the number of prior vaccine doses.

Results

Among 51 017 employees, COVID-19 occurred in 4424 (8.7%) during the study. In multivariable analysis, the bivalent-vaccinated state was associated with lower risk of COVID-19 during the BA.4/5-dominant (hazard ratio, 0.71 [95% confidence interval, .63–79]) and the BQ-dominant (0.80 [.69–.94]) phases, but decreased risk was not found during the XBB-dominant phase (0.96 [.82–.1.12]). The estimated vaccine effectiveness was 29% (95% confidence interval, 21%–37%), 20% (6%–31%), and 4% (−12% to 18%), during the BA.4/5-, BQ-, and XBB-dominant phases, respectively. The risk of COVID-19 also increased with time since the most recent prior COVID-19 episode and with the number of vaccine doses previously received.

Conclusions

The bivalent COVID-19 vaccine given to working-aged adults afforded modest protection overall against COVID-19 while the BA.4/5 lineages were the dominant circulating strains, afforded less protection when the BQ lineages were dominant, and effectiveness was not demonstrated when the XBB lineages were dominant.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, bivalent vaccine, effectiveness, vaccines

When the original messenger RNA (mRNA) coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines first became available in 2020, there was ample evidence of efficacy from randomized clinical trials [1, 2].Vaccine effectiveness was subsequently confirmed by clinical effectiveness data in the real world outside of clinical trials [3, 4], including an effectiveness estimate of 97% among employees within our own healthcare system [5]. This was when the human population had just encountered the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus, and the pathogen had exacted a high morbidity and mortality burden across the world. The vaccines were amazingly effective in preventing COVID-19, saved a large number of lives, and changed the impact of the pandemic.

Continued acquisition of mutations in the virus, from natural evolution in response to interaction with the immune response among the human population, led to the emergence and spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Despite this, for almost 2 years since the onset of the pandemic, those previously infected or vaccinated continued to have substantial protection against reinfection by virtue of natural or vaccine-induced immunity [6]. The arrival of the Omicron variant in December 2021 brought a significant change to the immune protection landscape. Previously infected or vaccinated individuals were no longer protected from COVID-19 [6]. Vaccine boosting provided some protection against the Omicron variant [7, 8], but the degree of protection was not near that of the original vaccine against the pre-Omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2 [8]. After the emergence of the Omicron variant, prior infection with an earlier lineage of the Omicron variant protected against subsequent infection with a subsequent lineage [9], but such protection appeared to wear off within a few months [10]. During the Omicron phase of the pandemic, protection from vaccine-induced immunity decreased within a few months after vaccine boosting [8].

Recognition that the original COVID-19 vaccines provided much less protection after the emergence of the Omicron variant spurred efforts to produce newer vaccines that were more effective. These efforts culminated in the approval by the US Food and Drug Administration, on 31 August 2022, of bivalent COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, which encoded antigens represented in the original vaccine as well as antigens representing the BA.4/5 lineages of the Omicron variant. Given the demonstrated safety of the earlier mRNA vaccines and the perceived urgency of need of a more effective preventive tool, these vaccines were approved without demonstration of effectiveness in clinical studies. The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether the bivalent COVID-19 vaccine protects against COVID-19.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted at the Cleveland Clinic Health System (Cleveland, Ohio) in the United States.

Patient Consent Statement

The study was approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board as exempt research (IRB no. 22–917). Waivers of informed consent and of HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) authorization were approved to allow the research team access to the required data.

Setting

Since the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic at Cleveland Clinic in March 2020, employee access to testing has been a priority. Voluntary vaccination for COVID-19 began on 16 December 2020, and the monovalent mRNA vaccine as a booster became available to employees on 5 October 2021. The bivalent COVID-19 mRNA vaccine was first offered to employees on 12 September 2022. This date was considered the study start date. The mix of circulating variants of SARS-CoV-2 changed over the course of the study. The majority of infections in Ohio were initially caused by the BA.4 or BA.5 lineages of the Omicron variant. By mid-December 2022 the BQ lineages, and by mid-January 2023 the XBB lineages of the Omicron variant were the dominant circulating strains [11].

Study Participants

The study included Cleveland Clinic Health System employees in employment at any Cleveland Clinic location in Ohio on 12 September 2022, the day the bivalent vaccine first became available to employees. Those for whom age and sex were not available were excluded.

Variables

The covariates collected were age, sex, job location, and job type categorized into clinical or nonclinical, as described in our earlier studies [5–7]. Institutional data governance rules related to employee data limited our ability to supplement our data set with additional clinical variables. Employees were considered prepandemic hires if hired before 16 March 2020, the day COVID-19 testing became available in our institution, and pandemic hires if hired on or after that date.

Prior COVID-19 was defined as a positive nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) result for SARS-CoV-2 any time before the study start date. The date of infection for a prior episode of COVID-19 was the date of the first positive test for that episode of illness. A positive test >90 days after the date of a previous infection was considered a new episode of infection. Since the health system never had a requirement for systematic asymptomatic employee test screening, most positive test results would have been from tests done to evaluate suspicious symptoms. Some would have been tests done to evaluate known exposures or for preoperative or preprocedural screening. The pandemic phase (pre-Omicron or Omicron) during which a study participant had his or her last prior episode of COVID-19 was also collected as a variable, based on which variant/lineages accounted for >50% of infections in Ohio at the time [11].

Outcome

The study outcome was time to COVID-19, the latter defined as a positive NAAT result for SARS-CoV-2 any time after the study start date. Outcomes were followed up until 14 March 2023, allowing for evaluation of outcomes up to 26 weeks from the study start date.

Statistical Analysis

A Simon-Makuch hazard plot [12] was created to compare the cumulative incidence of COVID-19 in the bivalent-vaccinated and nonvaccinated states, by treating bivalent vaccination as a time-dependent covariate. Study participants were considered bivalent vaccinated 7 days after receipt of a single dose of the bivalent COVID-19 vaccine. Those whose employment was terminated during the study period before they had COVID-19 were censored on the date of termination. Curves for the nonvaccinated state were based on data while the bivalent vaccination status of participants remained “nonvaccinated.” Curves for the bivalent-vaccinated state were based on data from the date the bivalent vaccination status changed to “vaccinated.”

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were fitted to examine the association of various variables with time to COVID-19. Bivalent vaccination was included as a time-dependent covariate [13]. The study period was divided into BA.4/5-dominant, BQ-dominant, and XBB-dominant phases, depending on which group of lineages accounted for >50% of all COVID-19 infections at the time (based on variant proportion data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]) [11] and which group of lineages was most abundant in our internal sequencing data. Time-dependent coefficients were used to separate out the effects of the bivalent vaccine during the different phases.

The primary model included all study participants. The secondary model included only those with prior exposure to SARS-CoV-2 by infection or vaccination and evaluated the effect of bivalent vaccination with inclusion of time since most recent exposure to SARS-CoV-2 by infection or vaccination, to adjust for the effect of waning immunity on susceptibility to COVID-19. The possibility of multicollinearity in the models was evaluated using variance inflation factors. The proportional hazards assumption was checked using log(−log[survival]) versus time plots. Vaccine effectiveness was calculated from the hazard ratios (HRs) for bivalent vaccination in the models. The analysis was performed by N. K. S. and A. S. N. using the survival package and R software, version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) [13–15].

RESULTS

Of 51 982 eligible study participants, 965 (1.9%) were excluded because of missing age or sex. Of the remaining 51 017 employees included, 3294 (6.5%) were censored during the study because of termination of employment. By the end of the study, 13 134 (26%) had received the bivalent vaccine, which was the Pfizer vaccine in 11 397 (87%) and the Moderna vaccine in the remaining 1700. In all, 4424 employees (8.7%) acquired COVID-19 during the 26 weeks of the study.

Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of participants included in the study. Notably, this was a relatively young population, with a mean age of 42 years. Among these individuals, 20 686 (41%) had previously had a documented episode of COVID-19, and 13 717 (27%) had previously had an Omicron variant infection; 45 064 (88%) had previously received ≥1 dose of vaccine, 42 550 (83%) had received ≥2 doses, and 46 761 (92%) had been previously exposed to SARS-CoV-2 by infection or vaccination.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 51 017 Employees of Cleveland Clinic in Ohio

| Characteristic | Employees, No. (%)a |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 42.3 (13.4) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 38 052 (74.6) |

| Male | 12 965 (25.4) |

| Location | |

| Cleveland Clinic Main Campus | 20 495 (40.2) |

| Cleveland area regional hospitals | 12 039 (23.6) |

| Ambulatory centers | 8865 (17.4) |

| Cleveland Clinic Akron | 4301 (8.4) |

| Administrative centers | 4141 (8.1) |

| Cleveland Clinic Medina | 1176 (2.3) |

| Hire cohort | |

| Prepandemic | 34 509 (67.6) |

| Pandemic | 16 508 (32.4) |

| Human resources job classification | |

| Clinical | 25 795 (50.6) |

| Nonclinical | 25 222 (49.4) |

| Pandemic phase when most recent infection occurred | |

| Not previously infected | 30 331 (59.4) |

| Pre-Omicron | 6969 (13.7) |

| Omicron | 13 717 (26.9) |

| Time since most recent infection, mean (SD), d | 287 (220) |

| No. of prior vaccine doses | |

| 0 | 5953 (11.7) |

| 1 | 2514 (4.9) |

| 2 | 14 985 (29.4) |

| 3 | 23 607 (46.3) |

| 4 | 3850 (7.5) |

| 5 | 91 (<1) |

| 6 | 17 (<1) |

| Time since most recent vaccine, mean (SD), 3 | 319 (135) |

| Time since proximate SARS-CoV-2 exposure, mean (SD)b | 263 (142) |

Abbreviations: SARS-Cov-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome; SD, standard deviation.

aData represented no. (%) of employees unless otherwise indicated.

bExposure by infection or vaccination.

Risk of COVID-19 Based on Prior Infection and Vaccination History

The risk of COVID-19 varied by the phase of the epidemic in which the study participant’s last prior COVID-19 episode occurred. In decreasing order of risk were those never previously infected, those last infected during the pre-Omicron phase, and those last infected during the Omicron phase (Figure 1). The risk of COVID-19 also varied by the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses previously received. The higher the number of vaccines previously received, the higher the risk of contracting COVID-19 (Figure 2).

Cumulative incidence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) for study participants stratified by the pandemic phase when the participant’s last prior COVID-19 episode occurred. Day 0 was 12 September 2022, the date the bivalent vaccine was first offered to employees. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals are jittered along the x-axis to improve visibility.

Cumulative incidence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) for study participants stratified by the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses previously received. Day 0 was 12 September 2022, the date the bivalent vaccine was first offered to employees. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals are jittered along the x-axis to improve visibility.

Bivalent Vaccine Effectiveness

The cumulative incidence of COVID-19 was similar for the bivalent-vaccinated and non–bivalent-vaccinated states in an unadjusted analysis (Figure 3). In a multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model, adjusted for age, sex, hire cohort, job category, number of COVID-19 vaccine doses before study start, and epidemic phase when the last prior COVID-19 episode occurred, bivalent vaccination provided some protection against COVID-19 while the BA.4/5 lineages were the dominant circulating strains (HR, 0.71 [95% confidence interval (CI)], .63–.79; P <.001), and less protection while the BQ lineages were dominant (0.80 [.69–.94]; P= .005).

Simon-Makuch plot comparing the cumulative incidence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) for the bivalent-vaccinated and non–bivalent-vaccinated states. Day 0 was 12 September 2022, the date the bivalent vaccine was first offered to employees. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals are jittered along the x-axis to improve visibility.

A protective effect of bivalent vaccination could not be demonstrated while the XBB strains were dominant (HR, 0.96 [95% CI, .82–.1.12]; P = .59). Point estimates and 95% CIs for HRs for the variables included in the unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression models are shown in Table 2. The calculated overall bivalent vaccine effectiveness from the model was 29% (95% CI, 21%–37%) during the BA.4/5-dominant phase, 20% (6%–31%) during the BQ-dominant phase, and 4% (−12% to 18%) during the XBB-dominant phase. The multivariable analysis also found that, the more recent the last prior COVID-19 episode was the lower the risk of COVID-19, and the greater the number of vaccine doses previously received the higher the risk of COVID-19.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Associations With Time to Coronavirus Disease 2019

| Variable | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivalent-vaccinated stateb | ||||

| BA.4/5-dominant phase | .85 (.76–.95) | .005 | .71 (.63–.79) | <.001 |

| BQ-dominant phase | .98 (.85–1.14) | .81 | .80 (.69–.94) | .005 |

| XBB-dominant phase | 1.17 (1.01–1.36) | .04 | .96 (.82–1.12) | .59 |

| Age | 1.003 (1.000–1.005) | .02 | .997 (.995–1.000) | .046 |

| Male sexc | .78 (.72–.84) | <.001 | .75 (.70–.80) | <.001 |

| Pandemic hired | .92 (.86–.98) | .01 | .96 (.89–1.03) | .24 |

| Clinical jobe | 1.12 (1.05–1.18) | <.001 | 1.15 (1.09–1.23) | <.001 |

| Last prior infection phasef | ||||

| Pre-Omicron | 2.06 (1.85–2.31) | <.001 | 2.20 (1.97–2.46) | <.001 |

| No known prior infection | 2.35 (2.15–2.56) | <.001 | 2.55 (2.34–2.79) | <.001 |

| No. of prior vaccine dosesg | ||||

| 1 | 1.91 (1.57–2.32) | <.001 | 2.07 (1.70–2.52) | <.001 |

| 2 | 2.22 (1.92–2.56) | <.001 | 2.50 (2.17–2.89) | <.001 |

| 3 | 2.69 (2.35–3.09) | <.001 | 3.10 (2.69–3.56) | <.001 |

| >3 | 2.94 (2.50–3.45) | <.001 | 3.53 (2.97–4.20) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

aFrom a multivariable Cox-proportional hazards regression model, with bivalent-vaccinated state treated as a time-dependent covariate and time-dependent coefficients used to separate effects during the period of dominance of the Omicron BA.4/5, BQ, and XBB lineages.

bTime-dependent covariate.

cReference: female sex.

dReference: prepandemic hire.

eReference: nonclinical job.

fReference: Omicron.

gReference: 0 doses.

Bivalent Vaccine Effectiveness Among Those With Prior SARS-CoV-2 Infection or Vaccination

Among persons with prior exposure to SARS-CoV-2 by infection or vaccination, HRs for bivalent vaccination for individuals, after adjusting for time since proximate SARS-CoV-2 exposure, are shown in Table 3. Bivalent vaccination protected against COVID-19 during the BA.4/5-dominant phase (HR, 0.78 [95% CI, .70–.88; P <.001), but a significant protective effect could not be demonstrated during the BQ-dominant phase (0.91 [.78–.1.07]; P = .25) or the XBB-dominant phase (1.05 [.85–.1.29]; P= .66).

Table 3.

Associations With Time to Coronavirus Disease 2019 Among Study Participants With Prior Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV-2) Exposure, Adjusted for Time Since Proximate SARS-CoV-2 Exposure by Prior Infection or Vaccination

| Variablea | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Bivalent-vaccinated stateb | ||

| BA.4/5-dominant phase | .78 (.69–.87) | <.001 |

| BQ-dominant phase | .90 (.78–1.05) | .19 |

| XBB-dominant phase | 1.06 (.91–1.24) | .43 |

| Age | 1.004 (1.001–1.006) | .005 |

| Male sexc | .78 (.73–.84) | <.001 |

| Pandemic hired | 1.07 (.99–1.15) | .08 |

| Clinical jobe | 1.11 (1.05–1.18) | <.001 |

| Time since proximate SARS-CoV-2 exposuref | ||

| 91–180 d | 1.70 (1.45–1.99) | <.001 |

| 181–270 d | 1.88 (1.63–2.16) | <.001 |

| 271–365 d | 2.81 (2.45–3.21) | <.001 |

| >365 d | 2.15 (1.86–2.50) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

aThe number of prior vaccine doses was not included as a variable because its inclusion would have introduced significant multicollinearity into the model.

bTime-dependent covariate.

cReference: female sex.

dReference: prepandemic hire.

eReference: nonclinical job.

fReference: ≤90 days; this includes those previously vaccinated within 90 days but not those previously infected within 90 days, as the latter would not have qualified for inclusion until 90 days after their most recent infection.

DISCUSSION

This study found that the current bivalent vaccines were about 29% effective overall in protecting against infection with SARS-CoV-2 when the Omicron BA.4/5 lineages were the predominant circulating strains, and effectiveness was lower when the circulating strains were no longer represented in the vaccine. A protective effect could not be demonstrated when the XBB lineages were dominant. The magnitude of protection afforded by bivalent vaccination while the BA.4/5 lineages were dominant was similar to that estimated in another study using data from the Increasing Community Access to Testing national SARS-CoV-2 testing program [16].

The strengths of our study include its large sample size and its conduct in a healthcare system where very early recognition of the critical importance of maintaining an effective workforce during the pandemic led to devotion of resources to provide an accurate accounting of who had COVID-19, when COVID-19 was diagnosed, who received a COVID-19 vaccine, and when. The study method, treating bivalent vaccination as a time-dependent covariate, allowed vaccine effectiveness to be determined in real time.

The study has several limitations. Individuals with unrecognized prior infection would have been misclassified as previously uninfected. Since prior infection protects against subsequent infection, such misclassification would have resulted in underestimating the protective effect of the vaccine. However, there is little reason to suppose that prior infections would have been missing in the bivalent-vaccinated and nonvaccinated states at disproportionate rates. There might be concern that those who chose to receive the bivalent vaccine may have been more worried about infection and more likely to be tested when they had symptoms, thereby disproportionately detecting more incident infections among those who received the bivalent vaccine. We did not find an association between the number of COVID-19 tests done and the number of prior vaccine doses, however, suggesting that this was not a confounding factor. Those who chose to get the bivalent vaccine could have been those who were more likely to have lower risk-taking behavior with respect to COVID-19. This would have the effect of finding a higher risk of COVID-19 in the nonvaccinated state, thereby potentially overestimating vaccine effectiveness, because the lower risk of COVID-19 in the bivalent-vaccinated state could have been due to lower risk-taking behavior rather than the vaccine.

The widespread availability of home testing kits might have reduced detection of incident infections. This potential effect should be somewhat mitigated in our healthcare cohort because one needs a NAAT to get paid time off, providing a strong incentive to get a NAAT if one tests positive at home. Even if one assumes that some individuals chose not to follow up on a positive home test result with a NAAT, it is very unlikely that individuals would have chosen to pursue NAAT after receiving the bivalent vaccine more than before receiving it, at rates disproportionate enough to affect the study’s findings.

We were unable to distinguish between symptomatic and asymptomatic infections and had to limit our analyses to all detected infections. Variables that were not considered might have influenced the findings substantially. Time since last prior exposure to SARS-CoV-2 could not be included in the primary model owing to multicollinearity. It is possible that the association of number of prior vaccine doses with increased risk of infection may have been confounded by time since last prior exposure to SARS-CoV-2. There were too few severe illnesses for the study to determine whether the vaccine decreased severity of illness. Finally, our study was done in a healthcare population, and included no children and few elderly persons, and the majority of study participants would not have been immunocompromised.

A possible explanation for a lower-than-expected vaccine effectiveness is that a substantial proportion of the population may have had prior asymptomatic Omicron variant infection. About a third of SARS-CoV-2 infections have been estimated to be asymptomatic in studies performed in different places at different times [17–19]. If so, protection from the bivalent vaccine may have been masked because those with prior Omicron variant infection may have already been somewhat protected against COVID-19 by virtue of natural immunity. A seroprevalence study conducted by the CDC found that by February 2022, 64% of the 18–64-year age-group population and 75% of children and adolescents had serologic evidence of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection [20], with almost half of the positive serologic results attributed to infections occurring between December 2021 and February 2022, which would have predominantly been Omicron BA.1/BA.2-lineage infections. With such a large proportion of the population expected to have already been previously exposed to the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, it is possible that a substantial proportion of individuals may be unlikely to derive any meaningful benefit from a bivalent vaccine.

The association of increased risk of COVID-19 with more prior vaccine doses was unexpected. A simplistic explanation might be that those who received more doses were more likely to be individuals at higher risk of COVID-19. A small proportion of individuals may have fit this description. However, the majority of participants in this study were young, and all were eligible to have received ≥3 doses of vaccine by the study start date, which they had every opportunity to do. Therefore, those who received ❤ doses (46% of individuals in the study) were not ineligible to receive the vaccine but rather chose not to follow the CDC’s recommendations on remaining updated with COVID-19 vaccination, and one could reasonably expect these individuals to have been more likely to exhibit risk-taking behavior. Despite this, their risk of acquiring COVID-19 was lower than that that of participants those who received more prior vaccine doses.

Ours is not the only study to find a possible association with more prior vaccine doses and higher risk of COVID-19. During an Omicron wave in Iceland, individuals who had previously received ≥2 doses were found to have a higher odds of reinfection than those who had received <2 doses, in an unadjusted analysis [21]. A large study found, in an adjusted analysis, that those who had an Omicron variant infection after previously receiving 3 doses of vaccine had a higher risk of reinfection than those who had an Omicron variant infection after previously receiving 2 doses [22]. Another study found, in multivariable analysis, that receipt of 2 or 3 doses of am mRNA vaccine following prior COVID-19 was associated with a higher risk of reinfection than receipt of a single dose [7]. Immune imprinting from prior exposure to different antigens in a prior vaccine [22, 23] and class switch toward noninflammatory spike-specific immunoglobulin G4 antibodies after repeated SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination [24] have been suggested as possible mechanisms whereby prior vaccine may provide less protection than expected. We still have a lot to learn about protection from COVID-19 vaccination, and in addition to vaccine effectiveness, it is important to examine whether multiple vaccine doses given over time may not be having the beneficial effect that is generally assumed.

In conclusion, this study found an overall modest protective effect of the bivalent vaccine against COVID-19 while the circulating strains were represented in the vaccine and lower protection when the circulating strains were no longer represented. A significant protective effect was not found when the XBB lineages were dominant. The unexpected finding of increasing risk with increasing number of prior COVID-19 vaccine doses needs further study.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions. N. K. S.: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, data curation, software, formal analysis, visualization, writing (original draft preparation; reviewing and editing), supervision, and project administration. P. C. B.: Resources, investigation, validation, and writing (reviewing and editing). A. S. N.: Methodology, formal analysis, visualization, validation, and writing (reviewing and editing). J. F. S. and A. H.: Resources and writing (reviewing and editing). S. M. G.: Project administration, resources, and writing (reviewing and editing).

Contributor Information

Nabin K Shrestha, Department of Infectious Diseases, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

Patrick C Burke, Infection Prevention, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

Amy S Nowacki, Quantitative Health Sciences, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

James F Simon, Enterprise Business Intelligence, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

Amanda Hagen, Occupational Health, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

Steven M Gordon, Department of Infectious Diseases, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

References

1. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al.. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:2603–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al.. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:403–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Dagan N, Barda N, Kepten E, et al.. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in a nationwide mass vaccination setting. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:1412–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Haas EJ, Angulo FJ, McLaughlin JM, et al.. Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. Lancet 2021; 397:1819–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Shrestha NK, Nowacki AS, Burke PC, Terpeluk P, Gordon SM. Effectiveness of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines among employees in an American healthcare system. medRxiv [Preprint: not peer reviewed]. 10 August2021. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.06.02.21258231v1.

6. Shrestha NK, Burke PC, Nowacki AS, Terpeluk P, Gordon SM. Necessity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination in persons who have already had COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 75:e662–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Shrestha NK, Shrestha P, Burke PC, Nowacki AS, Terpeluk P, Gordon SM. Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine boosting in previously infected or vaccinated individuals (COVID-19). Clin Infect Dis 2022; 75:2169–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Andeweg SP, de Gier B, Eggink D, et al.. Protection of COVID-19 vaccination and previous infection against Omicron BA.1, BA.2 and Delta SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Commun 2022; 13:4738. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Altarawneh HN, Chemaitelly H, Hasan MR, et al.. Protection against the Omicron variant from previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:1288–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Malato J, Ribeiro RM, Fernandes E, et al.. Rapid waning of protection induced by prior BA.1/BA.2 infection against BA.5 infection. medRxiv [Preprint: not peer reviewed]. 15 November2022. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.08.16.22278820v1.

11. Lambrou AS., Shirk P, Steele MK, et al.. Genomic surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 variants: predominance of the delta (B.1.617.2) and Omicron (B.1.1.529) variants—United States, June 2021–January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022; 71:206–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Simon R, Makuch RW. A non-parametric graphical representation of the relationship between survival and the occurrence of an event: application to responder versus non-responder bias. Stat Med 1984; 3:35–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Therneau TM, Crowson C, Atkinson E. Using time dependent covariates and time dependent coefficients in the Cox model. 2021. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/vignettes/timedep.pdf. Accessed 8 May 2021.

14. Therneau TM, Grambsh PM. Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model. New York,NY: Springer International Publishing, 2000. [Google Scholar]

15. R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2022.

16. Link-Gelles R, Ciesla AA, Fleming-Dutra KE, et al.. Effectiveness of bivalent mRNA vaccines in preventing symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection—increasing community access to testing program, United States, September–November 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022; 71:1526–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Oran DP, Topol EJ. The proportion of SARS-CoV-2 infections that are asymptomatic : a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2021; 174:655–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. McDonald SA, Miura F, Vos ERA, et al.. Estimating the asymptomatic proportion of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the general population: analysis of nationwide serosurvey data in the Netherlands. Eur J Epidemiol 2021; 36:735–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Shang W, Kang L, Cao G, et al.. Percentage of asymptomatic infections among SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant-positive individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines (Basel) 2022; 10:1049. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Clarke KEN, Jones JM, Deng Y, et al.. Seroprevalence of infection-induced SARS-CoV-2 antibodies—United States, September 2021–February 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022; 71:606–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Eythorsson E, Runolfsdottir HL, Ingvarsson RF, Sigurdsson MI, Palsson R. Rate of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection during an Omicron wave in Iceland. JAMA Netw Open 2022; 5:e2225320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, Tang P, et al.. . COVID-19 primary series and booster vaccination and immune imprinting. medRxiv [Preprint: not peer reviewed]. 13 November 2022. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.10.31.22281756v1.

23. Cao Y, Jian F, Wang J, et al.. Imprinted SARS-CoV-2 humoral immunity induces convergent Omicron RBD evolution. Nature 2023; 614:521–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Irrgang P, Gerling J, Kocher K, et al.. Class switch toward noninflammatory, spike-specific IgG4 antibodies after repeated SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Sci Immunol 2023; 8:eade2798. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Article

- Open Access

- Published:

Real-world COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against the Omicron BA.2 variant in a SARS-CoV-2 infection-naive population

- Jonathan J. Lau,

- Samuel M. S. Cheng,

- Kathy Leung,

- Cheuk Kwong Lee,

- Asmaa Hachim,

- Leo C. H. Tsang,

- Kenny W. H. Yam,

- Sara Chaothai,

- Kelvin K. H. Kwan,

- Zacary Y. H. Chai,

- Tiffany H. K. Lo,

- Masashi Mori,

- Chao Wu,

- Sophie A. Valkenburg,

- Gaya K. Amarasinghe,

- Eric H. Y. Lau,

- David S. C. Hui,

- Gabriel M. Leung,

- Malik Peiris &

- Joseph T. Wu

Nature Medicine volume 29, pages 348–357 (2023)Cite this article

- 19k Accesses

- 8 Citations

- 161 Altmetric

- Metrics details

Abstract

The SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant has demonstrated enhanced transmissibility and escape of vaccine-derived immunity. Although first-generation vaccines remain effective against severe disease and death, robust evidence on vaccine effectiveness (VE) against all Omicron infections, irrespective of symptoms, remains sparse. We used a community-wide serosurvey with 5,310 subjects to estimate how vaccination histories modulated risk of infection in infection-naive Hong Kong during a large wave of Omicron BA.2 epidemic in January–July 2022. We estimated that Omicron infected 45% (41–48%) of the local population. Three and four doses of BNT162b2 or CoronaVac were effective against Omicron infection 7 days after vaccination (VE of 48% (95% credible interval 34–64%) and 69% (46–98%) for three and four doses of BNT162b2, respectively; VE of 30% (1–66%) and 56% (6–97%) for three and four doses of CoronaVac, respectively). At 100 days after immunization, VE waned to 26% (7–41%) and 35% (10–71%) for three and four doses of BNT162b2, and to 6% (0–29%) and 11% (0–54%) for three and four doses of CoronaVac. The rapid waning of VE against infection conferred by first-generation vaccines and an increasingly complex viral evolutionary landscape highlight the necessity for rapidly deploying updated vaccines followed by vigilant monitoring of VE.

Main

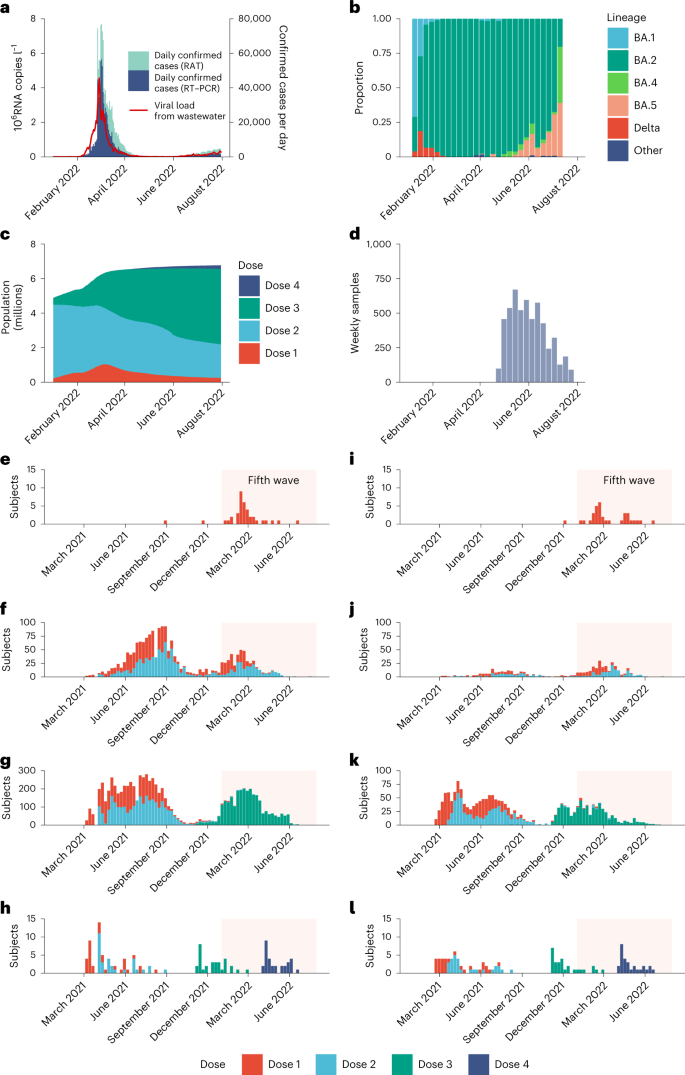

During 1 January to 31 July 2022, Hong Kong experienced an unprecedented fifth wave of COVID-19 infections driven predominantly by the Omicron BA.2 variant (B.1.1.529.2) with 1,341,363 reported cases (18.4% of the total population) and 9,290 deaths (0.7%)1. The fifth wave dwarfed the previous four waves in terms of cumulative infection attack rate (IAR), which was nearly zero before 2022 given Hong Kong’s then-successful ‘dynamic Zero-Covid’ strategy. Thus, population immunity to SARS-CoV-2 was almost entirely vaccine-derived when the fifth wave began. The messenger RNA vaccine Comirnaty (BNT162b2 mRNA, BioNTech/Fosun-Pharma) and the inactivated CoronaVac vaccine (Sinovac Life Sciences) have been available free of charge to Hong Kong residents aged 18 and above from 26 February 2021. Since then, eligibility to receive BNT162b2 or CoronaVac had been gradually extended to adolescents and children aged 6 months or above, and boosters to adolescents aged 12 years or above. Population uptake of at least two doses of either vaccine increased from 4.7 million (64% of the total population) by 1 January 2022 to 6.5 million (89%) by 31 July 2022 (ref. 1).

We conducted a community-wide serosurvey to estimate: (1) age-specific IAR in the fifth wave; (2) age-specific population immunity in the fifth wave; and (3) VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection conferred by two, three and four homologous doses of BNT162b2 or CoronaVac for 100 days after each dose. Specifically, for each subject in our serosurvey, we estimated the probability of being infected by SARS-CoV-2 before study recruitment, given age, vaccination record and seropositivity of the serum sample (Methods). Correspondingly, we defined VE as the reduction in the probability of being infected by SARS-CoV-2 within the observation period, as conferred by the type and doses of vaccine received by the subject, relative to the probability of infection for an unvaccinated subject in the same period. Our estimates of VE and waning were specific to infection by Omicron BA.2 only because almost all COVID-19 infections in Hong Kong before our study period were BA.2. We assumed that: (1) daily age-specific force of infection (FOI) was proportional to daily viral load from city-wide wastewater surveillance (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1), which has been shown to be a robust (normalized) proxy for disease prevalence over time2,3,4; and (2) one-dose vaccination provided no protection against infection and each successive homologous dose conferred greater VE that decayed exponentially over time at the same rate between doses of the same vaccine5.

Results

Our serosurvey subjects included: (1) 5,173 healthy adult blood donors recruited from the Hong Kong Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service between 28 April and 30 July 2022; and (2) 137 children aged 18 months to 11 years randomly recruited from the community to participate in an independent polio seroepidemiology study (see Fig. 1d for sera collection history). Vaccination histories were available for 5,242 subjects (Fig. 1 and Table 1) from the Hong Kong Department of Health (98%) or self-report (2%). At the time of sample collection, 1,237 blood donors (24%) and 31 child subjects (23%) self-reported a previous infection.Table 1 Characteristics of study participants, April 2022 to July 2022 (n = 5,310), excluding 67 participants with non-BNT162b2 or non-CoronaVac, or undetermined, vaccination history and one participant with undetermined age

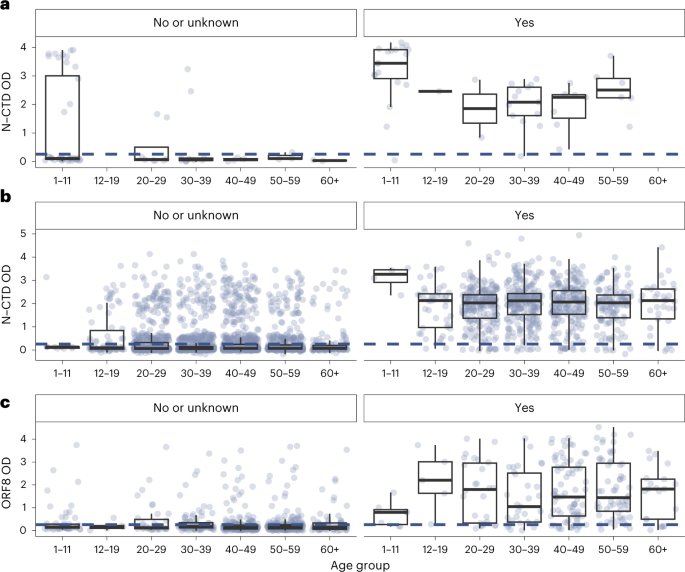

We developed two in-house enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) detecting immunoglobulin (Ig)G antibodies to the C-terminal domain of the nucleocapsid (N) protein (N-CTD) and the Open Reading Frame 8 protein (ORF8) of SARS-CoV-2, respectively, modifying and validating previously reported methods6,7. We estimated that our N-CTD assay was more than 95% sensitive and 96% specific in detecting recent Omicron infection among unvaccinated individuals and homologous BNT162b2 vaccinees. Because the inactivated whole-virus vaccine CoronaVac elicits antibody to the N protein, the ORF8 assay was optimized specifically for discriminating between infection and vaccine-derived antibody in CoronaVac vaccinees. We estimated that our ORF8 assay was 81% sensitive and 93% specific in detecting recent Omicron infection among homologous CoronaVac vaccinees. See Extended Data Fig. 2 for a mapping of vaccination cohort by assay. See Methods, Fig. 2 and Extended Data Fig. 3 for further details on assay workflow, performance and output. To our knowledge, our ORF8 assay is the first serological test that could effectively detect and discriminate recent SARS-CoV-2 infection from vaccination among CoronaVac vaccinees.

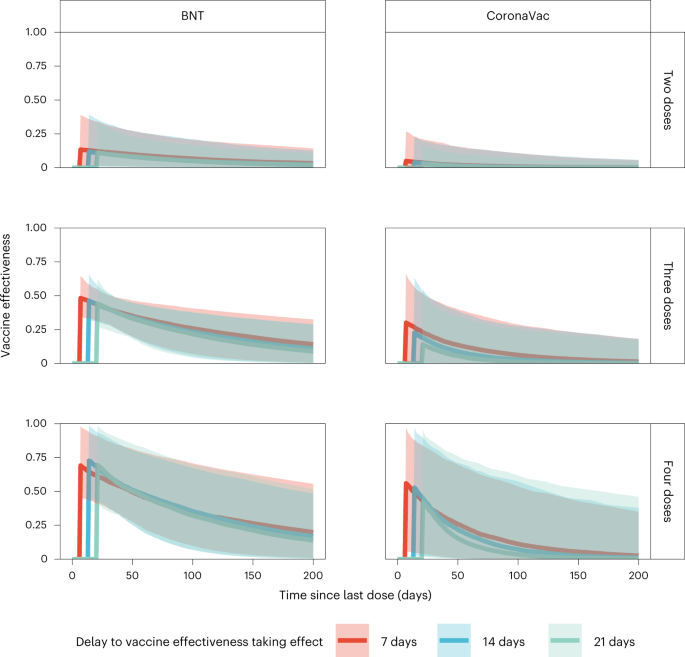

Assuming VE took full effect 7 days after vaccination, we estimated: (1) VE for the second, third or fourth doses of BNT162b2 were 13% (95% credible interval: 2–39%), 48% (34–64%) and 69% (46–98%) 7 days following immunization, respectively, waning to 7% (1–21%), 26% (7–41%) and 35% (10–71%) 100 days after immunization; and (2) VE for the second, third or fourth dose of the CoronaVac vaccine were 5% (0–27%), 30% (1–66%) and 56% (6–97%) 7 days following immunization, respectively, waning to 1% (0–11%), 6% (0–29%) and 11% (0–54%) 100 days after immunization.

Studies conducted during Omicron BA.1/BA.2 dominance and involving three adult doses8, four adult doses9 or two adolescent (12–17 years old) doses10 of BNT162b2 vaccination indicated full build-up of VE between 7–21 days (adults) and 14–27 days (adolescents) after the last dose. No data on VE build-up over time was available for CoronaVac, although serum neutralizing antibody titers peaked at around 2–3 weeks after homologous CoronaVac vaccination11. We selected a 7-day delay as our base case because the likelihood value in the inference decreased with longer delay. Nonetheless, we carried out sensitivity analyses assuming VE took effect 14 or 21 days after immunization, which yielded similar VE and waning estimates over time (Fig. 3). Because of the slow rise in cases from late June to the end of July, contemporaneous with the emergence of the BA.4/BA.5 variants (Fig. 1a,b), we performed further sensitivity analyses including only specimens collected by 15 June 2022, which also yielded similar results (Extended Data Fig. 4).

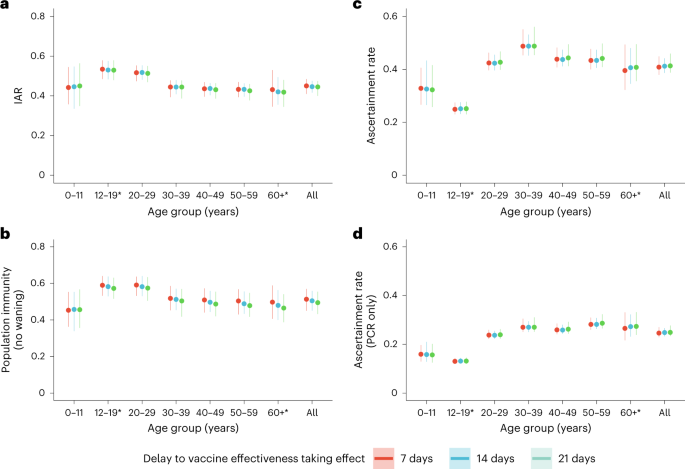

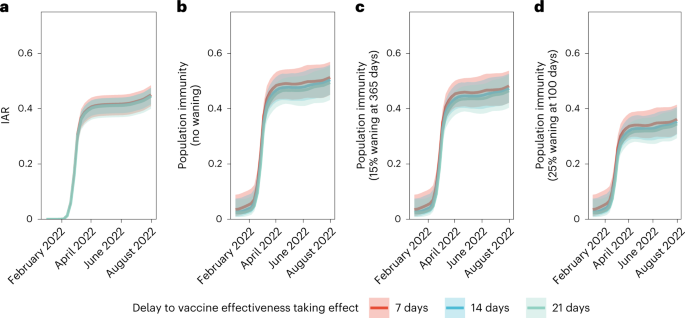

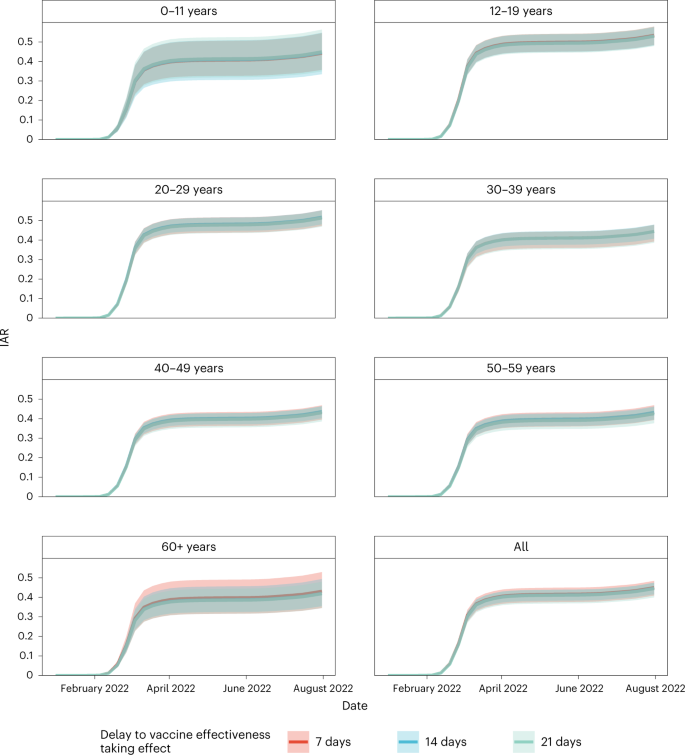

We then estimated age-specific IARs and population immunity over time, together with ascertainment ratios from polymerase chain reaction with reverse transcription (RT–PCR) testing and rapid antigen testing (RAT) using the approach detailed in the Methods. In brief, we first proxied the city-wide FOI via viral load data from wastewater surveillance, adjusted for age effect and calibrated against seropositivity among our unvaccinated study subjects. We then applied our estimates of VE and waning to the (anonymized) vaccination records for every individual in the population provided by the Hong Kong government to derive the probability of infection for each individual until 31 July 2022. Age-specific IARs were then derived by aggregating these probabilities and segmenting into age groups (Figs. 4, 5a and 6). Via this approach, we estimated that SARS-CoV-2 (predominantly Omicron BA.2) infected 45% (41–48%) of the population between 1 January and 31 July 2022. Adolescents and young adults had slightly higher IARs than other age groups. Assuming VE took effect after a 14- or 21-day delay yielded similar IAR estimates. Overall ascertainment ratio was 25% (23–27%) from RT–PCR testing alone, increasing to 41% (38–45%) if augmented with RAT (Fig. 4).

Meanwhile, we defined population immunity as the fraction of the population protected against Omicron BA.2 infection owing to previous infection or vaccination12,13, which was equivalent to the relative reduction in the effective reproduction number Rt conferred by natural and vaccine-induced immunity at any given time t. Protection conferred by vaccination was assessed based on our estimates of VE and waning. For each individual, we also calculated their probability of infection. We assumed that vaccination-induced and naturally acquired immunity were independent14, and that natural infection (with or without previous vaccination) provided perfect protection against reinfection (at least in the short term until the end of our study on 31 July 2022). That is, we did not model the differential protection against reinfection after natural infection between unvaccinated and vaccinated individuals (‘hybrid’ immunity was not modeled).

We estimated population immunity reached 52% (45–57%) by 31 July 2022. Sensitivity analyses assuming exponentially decaying immunity from natural infection yielded population immunity of 48% (42–54%) or 36% (31–41%) if such naturally acquired immunity decayed to 85% in 365 days15 or to 75% in 100 days16,17, respectively (Fig. 5 and Extended Data Figs. 5–7). The former estimate of decay was used in medium-term modeling in the UK. The latter, swifter, estimate of decay reflected the emergence and immune escape of the Omicron BA.4/BA.5 variants approximately 3 months after BA.1/BA.2 peaked in Portugal and Qatar—a time frame similar to that experienced in Hong Kong by late July 2022.

Discussion

Estimating VE against Omicron infection has been challenging in populations that have experienced widespread infection by older variants, owing to difficulties in disentangling the protective effect of vaccine-derived immunity from that of immunity derived from previous infection and ‘hybrid’ immunity. Although the test-negative design has been increasingly used to estimate VE against COVID-19, the robustness of the resulting estimates are typically conditional on symptoms and susceptible to confounding and selection bias (for example, owing to differential healthcare-seeking behavior)18. Furthermore, most VE estimates hitherto have estimated protection against symptomatic disease, hospitalization or death but not against all infections including asymptomatic infections. Our estimates of VE against Omicron BA.2 infection are robust against the abovementioned limitations because Hong Kong had negligible infection-derived immunity against any SARS-CoV-2 before to January 2022, and the infection histories of our subjects were individually inferred based on their serological measurements (irrespective of history of symptoms, case confirmation or contact)19.

Our Omicron IAR estimates over time were lower than those reported in South Africa (58% in urban areas by April 2022)20, Denmark (66% by March 2022)21, Navarre, Spain (up to 59% by May 2022)22 and British Columbia, Canada (up to 61% by July–August 2022)23 likely reflecting the effectiveness of extensive public health and social measures imposed in Hong Kong during the fifth wave, such as a universal mask mandate with high community compliance, closure of all bars, and limits on opening hours and new ventilation requirements in all restaurants24, counteracted by the very high density of Hong Kong’s residential dwellings facilitating rapid aerosol transmission between apartments25.

Our estimates provide evidence of the short-term effectiveness against Omicron infection of a third or fourth dose of either the mRNA or inactivated vaccine. Slightly higher initial BNT162b2 VE followed by rapid waning has been reported in the literature for symptomatic or RT–PCR-confirmed Omicron BA.2 infection. For example, Chemaitelly et al. reported that effectiveness relative to an unvaccinated reference group against symptomatic infection after the second dose was 51.7% in the first 3 months and waned to ≤10% thereafter, increasing to 43.7% after a booster dose before waning again at similar rate8. Meanwhile, Gazit et al. reported a fourth dose of BNT162b2 was 65.1% more effective by the third week against RT–PCR-confirmed Omicron infection relative to a third dose among people aged 60 years or older, declining to 22.0% by the end of 10 weeks9, although lower effectiveness was reported in Magen et al.26 and Regev-Yochay et al.27 also using triple-vaccinated subjects as reference groups. An update to Regev-Yochay et al. reported that the fourth dose of BNT162b2 no longer conferred a statistically significant incremental benefit above the third dose 103–180 days after vaccination28, similar to our estimate of VE for BNT162b2 after 100 days.

By contrast, there are very limited data on CoronaVac VE against Omicron infection29. Our study provides the first estimate of real-world VE and waning against Omicron infection conferred by three or four doses of CoronaVac. A recent telephone survey in Hong Kong reported three doses of COVID-19 vaccination with either BNT162b2 or CoronaVac provided 52% protection against test-positivity by RT–PCR or RAT relative to unvaccinated individuals, but was unable to account for time since vaccination or for asymptomatic infection30. Two South American studies reported 38.2 and 39.8% VE from two doses of CoronaVac against symptomatic Omicron infection in children aged 3–5 and 6–11 years, respectively,29,31 also relative to unvaccinated individuals. As a caveat, we distinguish our definition of VE (the reduction in the probability of infection relative to that of an unvaccinated reference group, with infection detected by seropositivity) from the definitions used in the above studies (generally, the reduction in the incidence of infection among a vaccinated and/or boosted intervention arm relative to a reference arm of unvaccinated or less-vaccinated individuals, with infection detected by voluntary RT–PCR or RAT testing). The different definitions might have contributed to the differences between our VE estimates and those of the other studies cited above.

We previously reported markedly reduced serum neutralizing antibody titers against BA.2 among individuals recently vaccinated with three doses of CoronaVac compared with the wild-type virus, with antibody titers below the predicted protective threshold32. Thus, our estimate of VE against BA.2 infection elicited by three doses of CoronaVac appears greater than would be expected from neutralizing antibody titers. Indeed, a recent VE study of CoronaVac vaccine using a test-negative design during this same BA.2 epidemic in Hong Kong also observed robust protection from severe disease and death33. It is possible that neutralizing antibody titers underestimate protection conferred by whole-virus inactivated vaccines such as CoronaVac, which present multiple viral proteins to the host immune system that may protect via multiple pathways other than neutralizing antibodies, such as T cell immunity and antibody-dependent cytotoxicity6.

Nonetheless, we note that the rapid waning of VE over time from even four doses of intramuscular vaccination by monovalent mRNA or inactivated vaccines based on the original Wuhan strain demonstrates the limits of such vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission in the long run. Further, although boosting by BNT162b2 or CoronaVac restores strong protection against hospitalization and death33,34,35, the incremental effectiveness of BNT162b2 boosters against such outcomes waned over the course of 4–6 months34 for both adults and the elderly36. There are limited data on CoronaVac waning in the Omicron era, though VE against intensive care admission in Malaysia waned considerably among the elderly 3–5 months after the primary series during a period of Delta dominance37. If this finding is confirmed in other studies, surge booster vaccination to top-up protection against severe disease and death, particularly among the elderly, remains a key tool in reducing COVID-19’s burden on healthcare systems and mortality before anticipated waves of infections.

Since September 2022, bivalent mRNA vaccines encoding the BA.5 spike protein have become widely available. Early observational evidence on their real-world VE are emerging38. Further investigations are necessary to ascertain the VE and waning over time in the midst of our complex SARS-CoV-2 variant and immunity landscape.

Despite the potential of reformulated bivalent boosters in increasing population immunity before upcoming waves of infections, vaccine hesitancy has resulted in very slow uptake of the bivalent boosters since their introduction39. The quadruple threat of potentially rapid VE waning, poor vaccine uptake, the possibility for immune imprinting and increasing complex SARS-CoV-2 evolution with the potential for multiple antigenically distant lineages cocirculating simultaneously40 may also create formidable challenges in the formulation and rapid deployment of updated bivalent or multivalent vaccines in the near future. There is thus substantial impetus to accelerate the development of mucosal vaccines41 and/or universal sarbecovirus vaccines42 capable of inducing broad, durable immunity against different variants of SARS-CoV-2 (refs. 43,44) to break the chain of transmission and limit the absolute burden of severe disease and long-term sequelae (long covid)45 from high-levels of breakthrough COVID-19 infection.

Limitations

Our study has several important limitations. First, we assumed that the effect of vaccination history on contact patterns and mobility (that is, exposure to the virus), a potential confounder of VE estimates, was negligible. Second, we had no serum samples from individuals aged 12–17 years and only few samples from individuals aged >65 years. As such, our IAR estimates for these age groups were less robust compared with other age groups. We assumed the same IAR among those aged >65 because: (1) 18, 16 and 17% of those aged 60–69, 70–79 and >80 years were confirmed to have COVID-19 during the period 1 January to 31 July 2022 (ref. 1); and (2) testing was widely available during the fifth wave and hence the ascertainment ratio was likely to be similar among those aged >65 years. Given the dramatically higher incidence of severe disease and death among the elderly, booster vaccination schemes should continue to prioritize this age cohort, particularly in lower- and middle-income countries with limited vaccine supply.

Third, we were unable to provide estimates of VE against hospitalization, severe disease and death owing to the wide introduction of oral antivirals in both ambulatory and hospital settings on 26 February 2022 in Hong Kong. The antivirals were very effective in further reducing the risk of hospitalization and death among those aged >60 years, including those who were partially vaccinated46,47 or, in the case of Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir (Paxlovid), also those who were fully vaccinated and boosted and had received their most recent dose >20 weeks previously48. Any estimate of VE against such outcomes, regardless of study methodology, must therefore account for the use of oral antivirals among its study subjects. Because we did not have access to comprehensive population-level data on oral antiviral usage in Hong Kong (particularly those prescribed in outpatient settings) or complete data matching cases of severe disease and death against their vaccination history and use of oral antivirals, we were unable to derive accurate estimates of VE, which must account for the significant protective effect of oral antivirals.

Fourth, our analysis was primarily based on seroprevalence among blood donors and voluntary child participants recruited from the community in the polio seroepidemiology study who might be healthier and thus not be representative of the general population in terms of their infection history, potentially underestimating seroprevalence. Nonetheless, nations that have relied on blood donors to provide early estimates of seroprevalence have subsequently reported similar estimates among random population samples49 or commercial laboratory specimen remnants50. In Hong Kong, a separate study of 873 hospital patient plasma specimens detected 43% were anti-N seropositive and 23% were anti-ORF8 seropositive by May 2022 (ref. 51). Another separate phylogenetic model of population IAR using GISAID sequences uploaded from multiple laboratories in Hong Kong as input also arrived at upper estimates between 33 and 49% (13–100%) by the week of 16 April 2022, which was similar to our mean estimate of 40% in the same week52. These independent estimates provide confidence that our reliance on healthy blood donors and voluntary child participants did not result in a material underestimate of COVID-19 seroprevalence in the general population.

Fifth, the small number of CoronaVac vaccinees in our serosurvey together with the short duration of the fifth wave led to substantial uncertainty in our CoronaVac VE estimates.

Sixth, we were unable to estimate VE conferred by heterologous vaccinations (CoronaVac with BNT162b2 boosters or vice versa) because of the very small number of individuals with such vaccination history (heterologous boosters were not available in Hong Kong until late 2021). When estimating IAR, we assumed that VE for each dose in heterogenous vaccinees equals that of the corresponding dose in homologous vaccinees.

Seventh, because our positive controls comprise only confirmed or self-reported infections, the corresponding seropositivity threshold may not be sufficiently sensitive to detect individuals with asymptomatic or very mild infections, thereby underestimating IAR. Two large pre-Omicron seroepidemiological studies before the availability of vaccines have reported that 5% (ref. 53) or 20% (ref. 54) of confirmed cases may not seroconvert. We performed sensitivity analyses to estimate the increase in our IAR estimates assuming that 10% or 25% of infected individuals did not seroconvert (that is, corresponding to seroconversion rates of 90 and 75%) (Extended Data Fig. 8). A 90% seroconversion rate would increase our IAR estimate to 50% (46–52%), whereas a 75% seroconversion rate would increase our estimate to 59% (54–63%) by 31 July 2022.

Lastly, because most of our serum samples were collected during and after a period of BA.2 dominance, we were unable to estimate further accelerated VE waning due to the emergence of later variants such as BA.4/BA.5 by late July 2022 in Hong Kong.

In conclusion, our results indicate the short-term effectiveness of booster vaccination using either the mRNA or inactivated vaccine in preventing SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2 infection. As such, surge booster campaigns could be strategically used to rapidly boost population immunity before upcoming waves of infections. The comparatively lower IAR in Hong Kong also highlights the effect of supplementing vaccination campaigns with continued public health and social measures in disease transmission. Nonetheless, in light of the potential for waning of VE, antigenic imprinting and rapid viral evolution, frequently updated studies quantifying the protective effect of repeated booster vaccination, including with the new bivalent COVID-19 vaccines, are necessary for policymakers to develop effective booster vaccination strategies.

Methods

Data sources

Serosurveys conducted by the study team

As part of a community-based COVID-19 seroepidemiological study, we recruited healthy blood donors by convenience sampling at the five largest blood donation centers (Mongkok, Causeway Bay, Kwun Tong, Tsuen Wan and Shatin) of the Hong Kong Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service from 28 April to 30 July 2022. We also tested serum samples from participants in an independent polio seroepidemiology study targeting children aged 18 months to 10 years from 7 May to 5 August 2022. Child participants in the polio seroepidemiology study were recruited at random from the community via social media, website and word-of-mouth advertising. Blood donors were matched by the Hong Kong Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service and the Hong Kong Department of Health with official vaccination records via unique blood transfusion service donor identification numbers. The records were then anonymized and provided to the study team. Both blood donors and child participants were asked to self-report their vaccination and COVID-19 infection history (as confirmed by RT–PCR testing or RAT pursuant to Hong Kong government guidelines). In cases in which official vaccination records were unavailable (that is, those vaccinated outside Hong Kong), we relied on the donors’ self-reported vaccination history if provided. All child participants self-reported their vaccination and infection history.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Parental consent was obtained for all participants aged <18 years. Further, consent was obtained from the parents of child participants of the polio seroepidemiology survey to test collected sera for antibodies and/or biomarkers specific to a panel of pathogens other than polio, including but not limited to SARS-CoV-2, seasonal influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumovirus, adenovirus, rhinovirus, enterovirus and human parainfluenza virus. Blood donor participants received no compensation for their participation. Child participants received compensation of HK $1,000 for participating in the polio seroepidemiology study. Ethical approval for this study and the polio seroepidemiology study (including the use of samples collected therein for antibody or biomarker testing against nonpolio pathogens) were obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster/University of Hong Kong (IRB No. UW 20–132 and IRB No. UW 21–196, respectively).

Vaccination records, confirmed cases and sewage surveillance data provided by the Hong Kong government

Official vaccination records in Hong Kong are maintained by the Hong Kong Department of Health55. Anonymous data on every vaccination up to 31 July 2022, including the date of each dose, type of vaccine (BNT162b2 or CoronaVac) used and vaccinee year-of-birth, were compiled by the Department of Health and provided to us by the Hong Kong Office of the Government Chief Information Officer. Age data on all confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases were provided by the Centre for Health Protection. Daily per capita 2-day running geometric mean SARS-CoV-2 viral load data (in copies of SARS-CoV-2 RNA l−1) obtained from city-wide COVID-19 wastewater surveillance up to 31 July 2022 were provided by the Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department. The 2022 projected mid-year population in each age cohort was obtained from the Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department56.

Laboratory methods

We developed two in-house ELISA assays that detected IgG antibodies to N-CTD and ORF8 (ref. 57) of SARS-CoV-2, respectively, modifying the methodology reported in Mok et al.6 and Hachim et al7. The ORF8 assay was developed specifically for detecting past Omicron BA.2 infections in CoronaVac vaccinees because most of them were N-CTD-seropositive owing to the immune response that CoronaVac elicits against the N protein. The ELISA assays as previously described6,7 were optimized and validated. In brief, 96-well ELISA plates (Nunc MaxiSorp, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were coated overnight with 40 ng well−1 of purified recombinant N-CTD protein in PBS buffer for the N-CTD protein ELISA assay or 30 ng well−1 of purified recombinant ORF8 protein in PBS buffer for the ORF8 ELISA assay. The plates were then blocked by 100 μl of Chonblock blocking buffer (Chondrex) per well and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Each serum sample was tested at a dilution of 1:100 in Chonblock blocking buffer in duplicate. The serum dilutions were added and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. After extensive washing with PBS containing 0.2% Tween 20, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (1:5,000; GE Healthcare) was added and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The ELISA plates were then washed again with PBS containing 0.2% Tween 20. Subsequently, 100 μl of horseradish peroxidase substrate (Ncm TMB One; New Cell and Molecular Biotech) was added into each well. After 15 min incubation, the reaction was stopped by adding 50 μl of 2 M H2SO4 solution and analyzed on a microplate reader at 450 nm wavelength. Positive and negative controls were included in each run.

This resulted in cutoffs of 0.2583 and 0.33 optical density (OD) for N-CTD and ORF8, respectively. The assays and cutoffs were validated against pre-pandemic blood donor samples, blood samples from homologous BNT162b2- or CoronaVac-vaccinated individuals collected during periods of minimal community transmission in 2020 and 2021, blood samples collected from RT–PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 convalescent individuals in 2020 and 2021, and samples from blood donors in the current study with self-reported infection history. See Extended Data Fig. 3 for details on control groups and assay performance (sensitivity, specificity and receiver operating curves). We set the ELISA cutoffs to approximately maximize the sum of sensitivity and specificity, which were in turn estimated via bootstrapping 2,000 samples using the pROC R package58, with specificity set not lower than 90%.

We did not account for waning of N-CTD and ORF8 antibody response. Nonetheless, we previously reported that N- and ORF8-specific antibody responses were well maintained for at least 100 days postinfection7. This is on par with the time elapsed between infection (for example, the fifth wave peaked in early March 2022) and the time of sample collection (between late April and July 2022) for our serosurvey subjects.

Statistical methods

Statistical inference of VE

Let VEv,j(u) be the VE of vaccine type v (B for BNT162b2 and C for CoronaVac) against infection u days after the jth dose in a homologous series has taken effect. For each vaccine type v, we assumed: (1) the first dose provided no protection against infection, that is VEv,1(u)=0 (ref. 59); (2) VEv,j(0) depended on the number but not the time of previous doses; (3) VE waned exponentially at a constant rate λv after each dose5,60,61,62, that is VEv,j(u)=VEv,j(0)×exp(−λvu); and (4) VEv,j(0) increased with each successive dose in a homologous series, that is VEv,j+1(0)>VEv,j(0) (refs. 26,63,64,65). We also assumed that the initial VE of two-dose BNT162b2 was not inferior to that of two-dose CoronaVac, that is VEB,2(0)≥VEC,2(0)

(the latter was not statistically identifiable otherwise).

Let time 0 be 1 January 2021. We assumed that the FOI at time t was proportional to the viral load per capita from city-wide sewage. Specifically, given an individual aged a with vaccination history H who remained uninfected at time t, her FOI at that time was

λ(t)=γ×f(a)×VL(t)×VEv,n(t)(t−Tn(t))

where:

- (1) f(a) was the effect of age on FOI with f(35) = 1 (those aged 35 years were the reference group). We assumed that: (1) f(a) was a piecewise cubic Hermite interpolating polynomial function for 10 ≤ a ≤ 65 with knots at 10, 18, 35, 50 and 65 years; and (2) f(a) = f(10) for a < 10 and f(a) = f(65) for a > 65.

- (2) VL(t) was the two-day running geometric mean viral load per capita from city-wide sewage.

- (3) n(t) was the total number of doses of vaccine type v that the individual had received up to time t and Tn(t) was the time at which the most recent dose took effect.

- (4) γ was a scaling factor (subject to statistical inference; Supplementary Table 1).

The probability that this individual was infected between time 0 and t was pinfection(t|a,H)=1−exp(−∫t0λ(u)du)

. If tested at the time t, this individual would be seropositive with probability

pseropositive(t|a,H)=qsens,v×pinfection(t|a,H)+(1−qspec,v)×(1−pinfection(t|a,H))

where qsens,v and qspec,v

were the sensitivity and specificity of the serological assay that we used to infer previous Omicron infections for individuals vaccinated with vaccine type v.

Let θ denote the set of model parameters subject to statistical inference (Supplementary Table 1). Let D denote the data available for inferring θ which comprised:

- (1) The age, vaccination history and time of serum collection of each subject i in the serosurvey. These data were used to calculate the probability of seropositivity of the serum sample collected from subject i (pseropositive,i

) via the abovementioned model. (2)

The observed seropositivity of the serum sample for each subject i in the serosurvey (τi = 1 if seropositive and τi = 0 otherwise). (3)

The number of positive and negative controls for estimating the sensitivity and specificity of our in-house ELISA assays among individuals with different vaccination history (nsens,v and nspec,v) and the respective number of seropositive samples (ysens,v and yspec,v

- ). See Extended Data Fig. 3 for details.

We used the following likelihood function to infer θ from D:

L(θ|D)=∏i∈SerosurveyBernoulli(τi|pseropositive,i)×∏v∈{U,B,C}Binomial(ysens,v|nsens,v,qsens,v)×∏v∈{U,B,C}Binomial(yspec,v|nspec,v,1−qspec,v)

where Bernoulli(⋅|p) was the Bernoulli pdf with parameter p, Binomial(⋅|n,q)

was the Binomial pdf with n trials and success probability q. The statistical inference was performed in a Bayesian framework with noninformative (flat) priors using Markov Chain Monte Carlo with Gibbs sampling. We used P(θ) to denote the posterior distribution of θ obtained from fitting the model to the data D.

Estimating IAR and population immunity

We randomly drew 300 samples of θ from P(θ). For each sample of θ drawn, we calculated pinfection,i(t) (cumulative probability of infection) and REi(t)+(1−pinfection,i(t))×VEv,j(t)

(expected immunity) for each individual in the general population given their vaccination record (as done for our serosurvey subjects) on days t at weekly intervals between 1 January and 31 July 2022. The protection conferred by previous infection against reinfection on day t is:

REi(t)=∫t0p′infection,i(τ)×exp(−κ(t−τ))dτ

where:

- (1) p′infection,i(τ)=λ(τ)exp(−∫τ0λ(u)du)

- is the probability of getting infected at time τ

- (2) κ is the waning rate of immunity conferred by previous infection.

Three κ scenarios were considered: (1) κ = 0 (base case, no waning); (2) κ=−log(0.85)/365 (corresponding to the ‘high waning’ scenario of 15% in one year in Barnard et al.15); and (3) κ=−log(0.75)/100

(corresponding to a 25% loss of protection within 100 days as observed in Portugal16 and Qatar17 upon BA.4/BA.5 emergence).

Posterior medians and 95% credible intervals of age-specific IARs and population immunity were compiled accordingly.

For individuals with heterologous CoronaVac and BNT162b2 vaccinations, we assumed VE for each dose was the same as that of the corresponding type and dose in a homologous series. We substituted missing records for intervening or preceding doses with the vaccine type of the next recorded dose, with a 90-day gap between the third and fourth doses, 180-day gap between the second and third doses or a 14-day gap between the first and second doses as per Hong Kong government recommendations before 31 May 2022. We derived the number of unvaccinated individuals in each age cohort based on the 2022 predicted mid-year population per the Census and Statistics Department56.

Lastly, we calculated the median and 95% confidence intervals of IARs, population immunity and ascertainment ratios by age group. We further performed sensitivity analyses incorporating the posterior distribution corresponding to 2-week (14 days) or a 3-week (21 days) delay for VE to take effect after each dose (Figs. 3–6 and Extended Data Figs. 5–7).

All analyses were performed using MATLAB 2022a with the Parallel Computing and Econometrics toolboxes and R v.4.2.1, with the tidyverse (v.1.3.2), pROC (v.1.18.0), cowplot (v.1.1.1) and janitor (v.2.1.0) packages.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The anonymized vaccination record data were compiled by the Office of the Government Chief Information Officer (OGCIO) (enquiry@ogcio.gov.hk) and the Department of Health (enquiries@dh.gov.hk), The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Age data for confirmed cases were compiled by the Centre for Health Protection (enquiries@dh.gov.hk). Data on viral load from sewage surveillance were compiled by the Environmental Protection Department, The Government of HKSAR (enquiry@epd.gov.hk). The aforementioned data could not be shared due to confidentiality undertakings to the above-named agencies. Interested parties could contact these agencies for access to these data. Request for access to anonymized serology output data may be directed to the corresponding author. However, as this data is matched to vaccination records covered by the aforementioned confidentiality undertaking, access is also subject to preapproval by the above-named agencies of The Government of HKSAR. Outputs of our analysis and source data for Figs. 3–6 and Extended Data Figs. 1 and 4–8 are accessible at https://github.com/jonathanjlau-hku/hkserosurvey2022.

Code availability

All code files are accessible at https://github.com/jonathanjlau-hku/hkserosurvey2022.

References

- Statistics on 5th Wave of COVID-19 (from 31 Dec 2021 up till 31 Jul 2022 00:00) (The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, 2022); https://www.coronavirus.gov.hk/pdf/5th_wave_statistics/5th_wave_statistics_20220731.pdf

- Modelling the Fifth Wave of COVID-19 in Hong Kong – Update #9 (The Univ. of Hong Kong, 2022); https://www.med.hku.hk/en/news/press//-/media/HKU-Med-Fac/News/slides/20220314-sims_wave_5_omicron_2022_03_14_final.ashx

- Morvan, M. et al. An analysis of 45 large-scale wastewater sites in England to estimate SARS-CoV-2 community prevalence. Nat. Commun. 13, 4313 (2022).PDF opens in a new tabArticle CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Amman, F. et al. Viral variant-resolved wastewater surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 at national scale. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 1814–1822 (2022).PDF opens in a new tabArticle CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Khoury, D. S. et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 27, 1205–1211 (2021).PDF opens in a new tabArticle CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Mok, C. K. P. et al. Comparison of the immunogenicity of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac COVID-19 vaccines in Hong Kong. Respirology 27, 301–310 (2022).PDF opens in a new tabArticle PubMed Google Scholar

- Hachim, A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 accessory proteins reveal distinct serological signatures in children. Nat. Commun. 13, 2951 (2022).PDF opens in a new tabArticle CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Chemaitelly, H. et al. Duration of mRNA vaccine protection against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 subvariants in Qatar. Nat. Commun. 13, 3082 (2022).PDF opens in a new tabArticle CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Gazit, S. et al. Short term, relative effectiveness of four doses versus three doses of BNT162b2 vaccine in people aged 60 years and older in Israel: retrospective, test negative, case-control study. BMJ 377, e071113 (2022).Article PubMed Google Scholar

- Florentino, P. T. V. et al. Vaccine effectiveness of two-dose BNT162b2 against symptomatic and severe COVID-19 among adolescents in Brazil and Scotland over time: a test-negative case-control study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 1577–1586 (2022).Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Li, X. et al. Long-term variations and potency of neutralizing antibodies against Omicron subvariants after CoronaVac-inactivated booster: a 7-month follow-up study. J. Med. Virol. 95, e28279 (2022).PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Moghadas, S. M., Sah, P., Shoukat, A., Meyers, L. A. & Galvani, A. P. Population immunity against COVID-19 in the United States. Ann. Intern. Med. 174, 1586–1591 (2021).Article PubMed Google Scholar

- Klaassen, F. et al. Population immunity to pre-Omicron and Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variants in US states and counties through December 1, 2021. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20, ciac438 (2022). Google Scholar

- Sonabend, R. et al. Non-pharmaceutical interventions, vaccination, and the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant in England: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet 398, 1825–1835 (2021).Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Barnard, R. C., Davies, N. G., Jit, M. & Edmunds, W. J. Modelling the medium-term dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in England in the Omicron era. Nat. Commun. 13, 4879 (2022).PDF opens in a new tabArticle CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Malato, J. et al. Risk of BA.5 infection among persons exposed to previous SARS-CoV-2 variants. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 953–954 (2022).Article PubMed Google Scholar

- Altarawneh, H. N. et al. Effects of previous infection and vaccination on symptomatic omicron infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 21–34 (2022).Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

- Sullivan, S. G., Tchetgen Tchetgen, E. J. & Cowling, B. J. Theoretical basis of the test-negative study design for assessment of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Am. J. Epidemiol. 184, 345–353 (2016).PDF opens in a new tabArticle PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Chen, L. L. et al. Contribution of low population immunity to the severe Omicron BA.2 outbreak in Hong Kong. Nat. Commun. 13, 3618 (2022).PDF opens in a new tabArticle CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Sun, K. et al. Rapidly shifting immunologic landscape and severity of SARS-CoV-2 in the Omicron era in South Africa. Nat. Commun. 14, 246 (2023).PDF opens in a new tabArticle CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Erikstrup, C. et al. Seroprevalence and infection fatality rate of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in Denmark: a nationwide serosurveillance study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 21, 100479 (2022).Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar